Sonic Double

Moonah Arts Centre, 2024

2 person show with Claudine Arendt

Andrew Harper.

The Mercury Weekend, Feb 2024

One evening around 2014, on a train from Melbourne Central to Lilydale, my dad stood up in a reasonably full carriage and announced he was going to sing a song for everyone in honour of St Patricks day. He closed his eyes and tried to communicate the soul of the song to insular commuters. Everyone pretty much ignored him. I knew he wasn’t doing it for attention, nor aware he could be annoying people - he would have seen it as a public service. He lived alone in the big city, and missed the ritual of sharing old stories through song. He wanted to let the commuters in on the tradition. I cringed with embarrassment, though a small part of me felt endeared, remembering how in a different time and place I would have been taken away by the story in the song.

Growing up in Ireland, my family, and all the families I knew would sing at gatherings where drink was involved. Christmases, weddings, christenings, funerals, parties; when there was nothing left to chat about, songs were sung by one person at a time, acapella, as everyone listened. It didn’t matter if you had a nice singing voice (though it was a bonus), if you wanted to share asong, you sang. Many didn’t sing, but everyone listened.

It was usually old Irish folk songs, though sometimes popular tunes of the time, whatever the mood brought. But people listened more intently to the old songs. They had layers of ancestral weight, communicating stories of grief, rebellion, resilience and love passed along through history. People had ‘their’ song, or a collection of them, earned through repeated performing over the years, like a touchstone weaving significant times together. After a person passed away, you could sing their song to honour their memory, or it could become your song, if you were close enough to have inherited it. Often people would introduce it by saying, for example, “this was my mother’s song”.

My dad lived and worked overseas as there wasn’t much employment at home. His rare visits were the highlights of our childhood. I remember hearing him sing at the tail end of the welcome home gatherings, or sometimes through the thin ceiling/floor as I lay in bed at night.

Last year he died alone in Melbourne. It was sudden, and difficult to integrate mentally. He was always somewhere far away, now he is nowhere. Even with his body laid out, in the private moments to say goodbye, we sang to him. My brothers and I, and then my sister over the phone from Ireland, held up by my brother's trembling hand.

When clearing out his unit, I found recordings on his phone - rough voice notes of him singing by himself. It occurred to me this was the end of another layer of familial generation, and the songs have been passed along. It’s striking to me how the voice can hold all the familiarity of a fully formed human, a loved human. When listening it’s as though they are present again, mysteriously embodied in the vibrations and tones.

I felt compelled to add my voice to the recordings, with subtle layers to support and uplift his voice (kind of like a hug through song). Harmonies don’t come naturally to me. I find it incredibly difficult to turn my attention from the dominant melody, like a main road I’ve travelled too many times, and it keeps drawing me back as I try to carve out the laneways and backstreets to take a parallel journey. Much like the journey of grief, it requires me to hold the memory without ever looking for it in reality; a simultaneous focus and letting go. It’s a delicate balance, and very easy to put a foot wrong, to clash and create dissonance. There's a satisfaction to achieving the harmony - the sense of resolve, a ringing vibration that seems to regenerate the air around it. Creating harmony with the voice of one lost has been a balm for the grief.

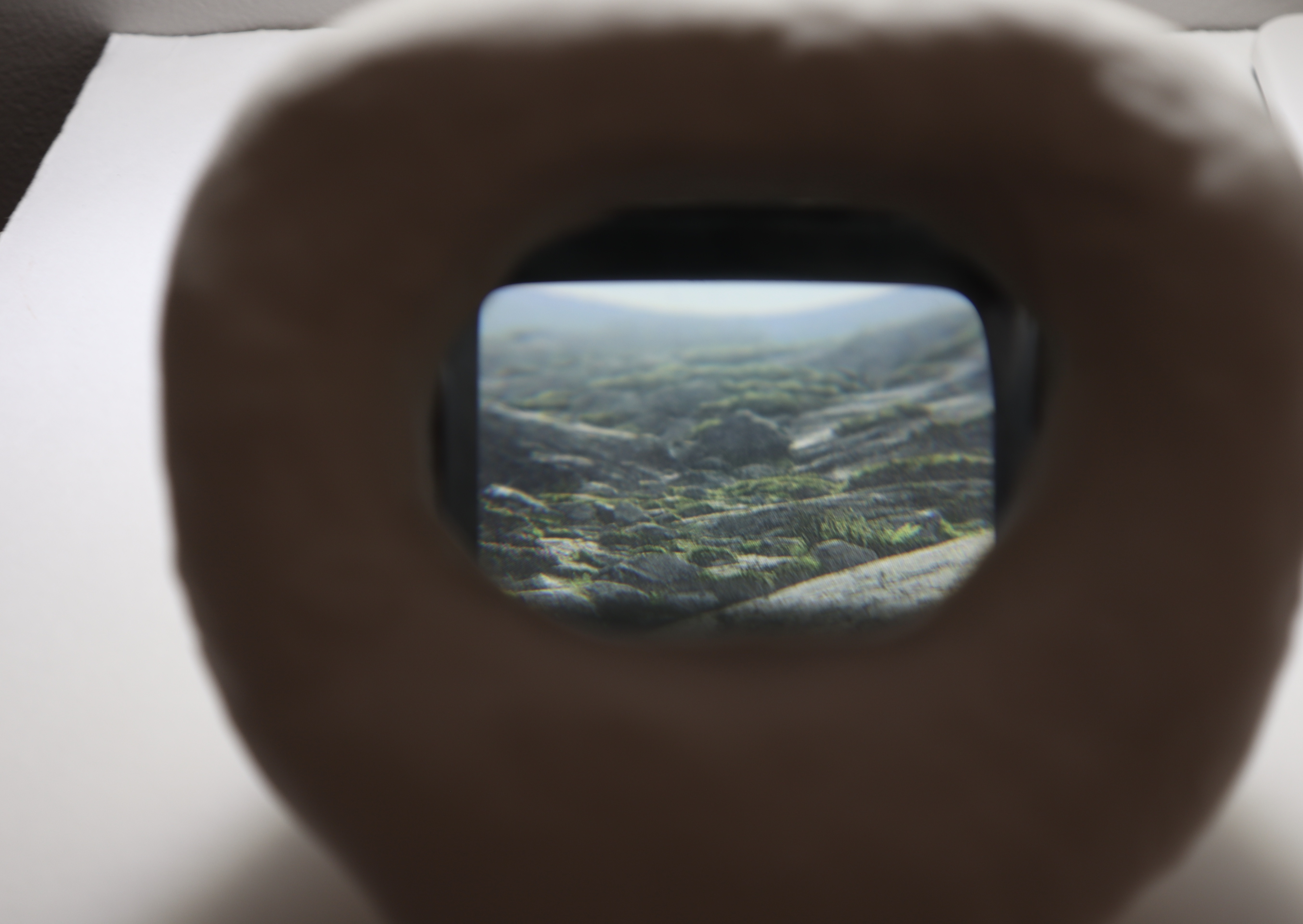

I vaguely planned to visit the Cliffs of Dooneen next time I’m in Ireland. I searched for where they may be found, though it seems ambiguous. According to one scholar, the cliffs in the song are not a physical place but ‘to be found in the mists of myth and nostalgia’. I may never get to the cliffs, but I can sing my dad’s song and continue weaving the layers.

–

Avondale (Dominic Behan) is about the birthplace of Charles Stuart Parnell, a revered Irish politician from the 1800s.

Only Her Rivers Run Free (Mickey MacConnell) laments the struggle for freedom and vitality under foreign occupation.

The Cliffs of Dooneen (Traditional/Jack McAuliffe) recounts love and nostalgia for one's homeland, from the perspective of a migrant.

Special Thank You to Richie Cuskelly and Harry Bird for their assistance with harmonising and recording.

Growing up in Ireland, my family, and all the families I knew would sing at gatherings where drink was involved. Christmases, weddings, christenings, funerals, parties; when there was nothing left to chat about, songs were sung by one person at a time, acapella, as everyone listened. It didn’t matter if you had a nice singing voice (though it was a bonus), if you wanted to share asong, you sang. Many didn’t sing, but everyone listened.

It was usually old Irish folk songs, though sometimes popular tunes of the time, whatever the mood brought. But people listened more intently to the old songs. They had layers of ancestral weight, communicating stories of grief, rebellion, resilience and love passed along through history. People had ‘their’ song, or a collection of them, earned through repeated performing over the years, like a touchstone weaving significant times together. After a person passed away, you could sing their song to honour their memory, or it could become your song, if you were close enough to have inherited it. Often people would introduce it by saying, for example, “this was my mother’s song”.

My dad lived and worked overseas as there wasn’t much employment at home. His rare visits were the highlights of our childhood. I remember hearing him sing at the tail end of the welcome home gatherings, or sometimes through the thin ceiling/floor as I lay in bed at night.

Last year he died alone in Melbourne. It was sudden, and difficult to integrate mentally. He was always somewhere far away, now he is nowhere. Even with his body laid out, in the private moments to say goodbye, we sang to him. My brothers and I, and then my sister over the phone from Ireland, held up by my brother's trembling hand.

When clearing out his unit, I found recordings on his phone - rough voice notes of him singing by himself. It occurred to me this was the end of another layer of familial generation, and the songs have been passed along. It’s striking to me how the voice can hold all the familiarity of a fully formed human, a loved human. When listening it’s as though they are present again, mysteriously embodied in the vibrations and tones.

I felt compelled to add my voice to the recordings, with subtle layers to support and uplift his voice (kind of like a hug through song). Harmonies don’t come naturally to me. I find it incredibly difficult to turn my attention from the dominant melody, like a main road I’ve travelled too many times, and it keeps drawing me back as I try to carve out the laneways and backstreets to take a parallel journey. Much like the journey of grief, it requires me to hold the memory without ever looking for it in reality; a simultaneous focus and letting go. It’s a delicate balance, and very easy to put a foot wrong, to clash and create dissonance. There's a satisfaction to achieving the harmony - the sense of resolve, a ringing vibration that seems to regenerate the air around it. Creating harmony with the voice of one lost has been a balm for the grief.

I vaguely planned to visit the Cliffs of Dooneen next time I’m in Ireland. I searched for where they may be found, though it seems ambiguous. According to one scholar, the cliffs in the song are not a physical place but ‘to be found in the mists of myth and nostalgia’. I may never get to the cliffs, but I can sing my dad’s song and continue weaving the layers.

–

Avondale (Dominic Behan) is about the birthplace of Charles Stuart Parnell, a revered Irish politician from the 1800s.

Only Her Rivers Run Free (Mickey MacConnell) laments the struggle for freedom and vitality under foreign occupation.

The Cliffs of Dooneen (Traditional/Jack McAuliffe) recounts love and nostalgia for one's homeland, from the perspective of a migrant.

Special Thank You to Richie Cuskelly and Harry Bird for their assistance with harmonising and recording.